Hog transportation in southwestern Ohio proved to have various difficulties. Hogs were bred and raised on farms in rural spaces, but packaging facilities, slaughter houses, and markets were located in Cincinnati, against the Ohio River. Moving pigs from farm to city posed a challenge for the farmers and merchants that needed hogs transported. Up until the 1840s, the method of transporting hogs from the farms to the stockyards was most often to walk the hogs from the farms to the stockyards. These drives would start as early as late November and continue past early January. Hogs had to be moved during these months to ensure that the hogs would not overheat and that the processed pork could stay fresh longer while being transported down river when colder weather would help preserve products. To transport the hogs farmers would often join together and set up a group of farm hands or hire people to walk the hogs to the stockyard. These individuals were called drovers. Drovers mainly walked during the drive. Some drives had drovers on horseback but these drovers would only be in the front and rear of the herd and an addition to drovers walking by foot. There were also drovers that would bring horse drawn carriages.Only a small number of drovers were responsible for a large number of free-roaming hogs. Recorded journeys suggest the drives would take fifteen to twenty days on average at a daily rate of five to ten miles. The herds would vary in size but the majority were two hundred to three hundred hogs. One of the largest herds reported was in Hamilton, Ohio in the 1830’s with 1,800 hogs.

Hogs walking freely would sometimes stray from the herd, drop weight, and stop walking to name a few examples. Drovers would go with the pace of the hogs encouraging them to move in the correct direction without great force to keep the hogs calm. Because pigs are social animals, large groups tended to handle better than small ones, and hogs were more inclined to stay together. The herds traveled about five to seven miles a day, depending on the weather and the terrain. Drovers preferred the ground to be wet and soft. Frozen surface had the tendency of cutting the hogs’ feet. A single drover, normally the boss would drive a wagon so they could haul supplies and transport hogs that were struggling to continue walking. In addition six or eight drovers, depending on the number of hogs, would make up the rest of the driving group.

Drovers dealt with various factors they could not control, in addition to the hogs. The weather conditions dramatically impacted the difficulty and length of the drives. Some hogs would give out and lay in mud, and when that happened drovers with a wagon would take these hogs into the wagon. There was no guarantee when or where drovers would get their hogs to market. Drovers would get held up by weather conditions including heavy rain, snowstorms, and severe frost. Rain was highly inconvenient because it reduced the roads and trails to mud which created hazardous conditions to walk the hogs. Heavy snow falls presented problems in acquiring enough feed to prevent weight loss and would create obstacles for travel. A sharp frost might harden the road surface and accelerate movement, but it also froze the rivers sufficiently to facilitate the passage to other markets. This created an opportunity for competition between packers and between cities. Due to the extensive outdoor travel the pork trade was seasonal. Good weather meant farmers would send larger numbers of hogs to Cincinnati while poor weather and a low market price meant a pause in the supply of hogs.

In the early days of hog drives Ohio had areas of dense forest landscape. Hog drives through these difficult terrains lead to the creation of various cleared paths. According to Oliver Johnson’s, an Indiana farmer in the 1840s, the trip from his farm outside of Indianapolis to the Cincinnati stockyards took fifteen to twenty days with the hogs while the return trip would take five days. Overtime, the repeated use of similar paths created various roads that are still utilized today. One path that is heavily used today is the Colerain Turnpike. As these roads became more defined, taverns opened for travelers including drovers. Often the taverns along these routes provided some type of fenced area for the hogs. Drovers would buy corn for the hogs at tavern stops, at a high price of about fifty cents per bushel. After setting up the hog herd in the pen drovers would get as clean as possible using a tub of water, eat and drink, and get sleep. Drovers would sleep on the floor as beds were rarely available.

By the 1850s the railroad industry had completely changed the hog industry in southwestern Ohio. Hogs that were transported by canal could now also be transported by train. “During the packing season of 1851 to 1852 less than 1/3 of Cincinnati’s livestock imports arrived by the canal, river, and rail. Only two years later the volume of these conveyances had almost doubled, and by 1856 the region’s three principal railroads had transported over 300,000 hogs. The railroad “saved time, and allowed hogs to be shipped at heavier weights and minimized weight loss seen on longer drives or canal journeys”. The hog industry could now expand outside of its seasonal range year round. No longer was weather a main factor controlling drives.

The railroad allowed a greater flow of the raw materials of production in the hog industry, and replaced the hog drive as the primary method of getting the hogs to market. The railroads did not, however, increase the success of Cincinnati’s pork industry. In the 1860’s the leading pork packing in the United States shifted from Cincinnati to Chicago. This was caused by multiple factors, including the competition among packing centers, Chicago has a better railroad main port setup compared to Cincinnati, and the declining demand for hogs . In the 1860’s Ohio Valley’s hog farmers were declining as cash crops, such as corn, could get a greater price than hogs.

The Bunker Hill Tavern

The Bunker Hill Tavern opened in 1832. The location started as a tavern but rapid success led to the expansion of the main building in both 1834 and 1838. The Bunker Hill Tavern became a social center for the Preble county residents and travelers passing through. It even had a dance room on the second floor where events would be held for locals and visitors. Most travelers were either people heading west or livestock drovers transporting animals to market. When drovers arrived they would herd their animals into the pens located within eyesight of the Bunker Hill Tavern. These pens were located next to a creek where the livestock and drovers could drink. In 1852 a railroad track was built along the opposite side of the creek following the valley.

Drovers would pay for a meal and to stay in the upstairs room of the tavern overnight to rest. These rooms were designed to hold multiple drovers at the same time. The Bunker Hill Tavern was a prime location for livestock transporters. It was located 20 miles from Hamilton, Richmond, and Cincinnati. A toll booth was located on what is known today as the OH-177, where a fee was collected based on how many animals were being transported.

In 1858 The Bunker Hill Tavern went bankrupt because the railroad significantly decreased their business. In 1862 the Bunker Hill Tavern became the Bunker Hill House when it was reopened and marketed as a general store. The Bunker Hill House was named a Historic Ohio Underground Railroad Site by the Friends of Freedom Society. Gabriel Smith was a free black man and the conductor of this Underground Railroad stop. Affectionately called Old Gabe, Gabriel was a musician that would play for those visiting the Bunker Hill Tavern. He shared his musical talents by teaching music. He was also a member of the Hopewell Church which also supported the Underground Railroad by creating a network to help enslaved people escape.

The Colerain Pike

The Colerain Pike was a significant part of many hog drives. This road was established as a result of the long term use of this created path by livestock drives and travelers. The Colerain Pike leads drovers directly to Cincinnati slaughter houses. Towards the end of drives to Cincinnati on the Colerain Pike, drovers and hogs had to cross the Great Miami River. The Great Miami River bridge allowed drovers and hogs to cross safely. By mid 1820, 40,000 hogs crossed the Miami Bridge in a year.

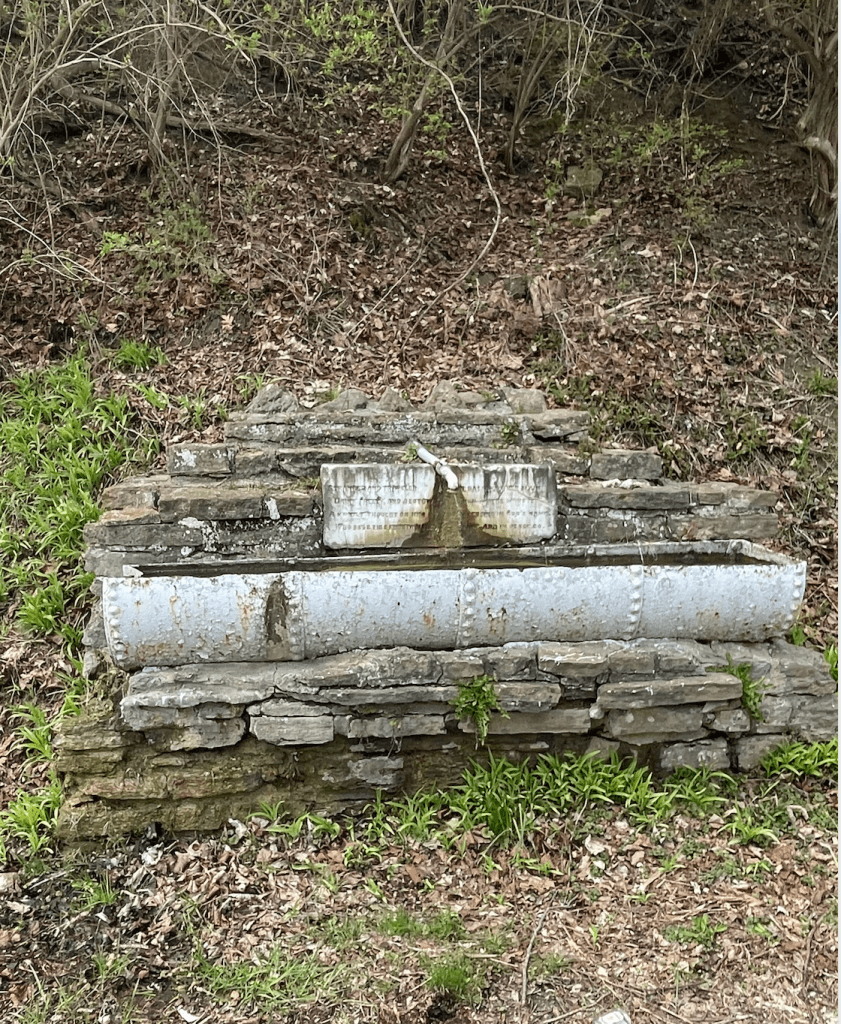

This image to the left is the Giles Richards water trough. Located along the Colerain Pike, this trough dates back to the 19th century. It supplies water to drovers and livestock.

The image to the left is of the modern-day Colerain Pike. This image is facing towards the Great Miami River