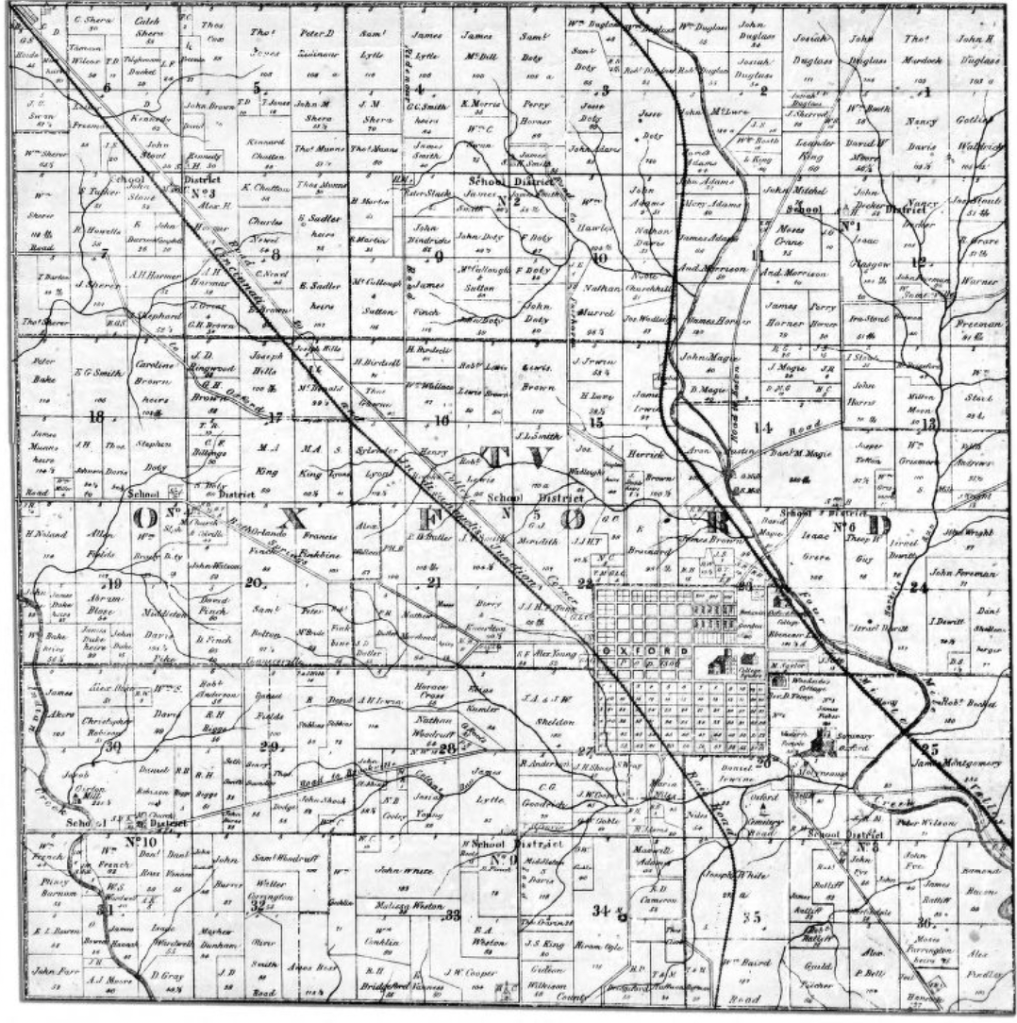

Map of Oxford Township Land Plots, 1855

Ohio’s prominent farming community was established long before the name Porkopolis was ever spoken. It is important to note that Cincinnati was not the only area drastically changed by this booming livestock industry. Farms originally were settlements where families would utilize the land to support the family unit directly. Family-sized food-producing farm units supported midwestern society. This fast-growing human population directly correlated to the fast-growing livestock population. In 1850 there were 1,519,000 people in the State of Ohio and 2,100,000 hogs; by 1860 there were 2,340,000 people and 2,252,000 hogs (Note numbers of people and hogs by population 1000).

Midwestern farmers also acted as packers, slaughtering hogs and curing the meat for personal use. This changed around 1818 when Elisha Mills opened and became the first commercial packer in the west, however there is evidence of smaller scale packers as early as 1811. Any additional meat was brought by the farmer to the local markets located on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Merchants bought the pork and prepare it to travel downriver to be sold. Numerous factors complicated this process; weather, amount of product, salt supply, and demand for hog products. Merchants also bought hogs directly from the farmers or drovers. As demand began to rise, the hog’s reputation as easy to raise appealed to early settlers with limited resources. Hogs gained a reputation as easy money. Farmers sought wealth by participating in the market economy by raising and selling hogs. Two types of hog farmers emerged as the pork packing industry boomed around 1820. Growers were usually small farmers, who raised a few animals at a time, while fatters maintained more significant operations, buying young hogs from growers and fattening them in large herds for market.

Raising hogs was convenient for farmers, especially corn farmers who created the corn hog cycle to ensure consistent profits. When corn was in low supply, a higher price could be demanded, making it worth keeping the corn to sell to the market. When corn was in high supply, it could be bought cheaply to fatten hogs, which were slaughtered and sold as pork products. Farmers realized minimal care could produce significant results in the hog’s ability to be prepared for the pork industry.

Atlas Map of Butler County Ohio, 1875

There are two distinct categories of hog: the lard type and the bacon type. The lard hog significantly outnumbered the bacon hog type in the United States in the 19th century because oil made from hog fat was a in high demand The lard type was often referred to as the American type due to it being the preferred type nationally. Lard hogs tended to be shorter and compact from a diet of corn. They produced large amounts of fat to be rendered into products, including: lubricants, soap, lamp, oil, cosmetics, and explosives. The Berkshire and Poland China were two famous lard-type hogs, both known for their meat quality and taste resulting from the fat content. Bacon hogs tended to be longer and leaner from their diet of protein and roughage. The Yorkshire and the Tamworth breeds fell under this category.As the demand for hogs increased to a larger market, farmers sought to meet the more specific needs of the market through hog genetics. Farmers introduced a variety of foreign hogs, such as the Suffolk, Berkshire, Yorkshire, Irish Grazer, Poland, Essex, Chinese, and Chester Whites, in the 1840s. Farmers bred the hogs based on qualities desired by consumers. Farmers could not create new hogs; they were restricted by the characteristics that were already part of the genetic pool. Therefore farmers used their knowledge of hogs characteristics both physically and behaviorally. Farmers relied on variations to breed hogs for a desired result.